Dreams in Celluloid, Part V

Dreyer is a master of minimal filmmaking. What he can do with minimal effort is astonishing – a technique which lends itself well to re-creating religious hysteria and moral ambiguities of his characters. The paranoia inherent within The Day of Wrath fills every scene with a quiet tension and overall sense of helplessness – a reflection of the Nazi’s occupation of Dreyer’s homeland of Denmark during the time of filming no doubt accentuated this effect. Few other directors are capable of recreating that sense of simmering disquiet with quite the same style. The closest I can think of is Clouzot’s Le Corbeau, but it lacks the intensity of Dreyer’s masterpiece.

“Terminate with extreme prejudice.”

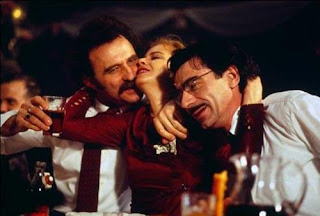

Everything about this films screams big, the opening shots of the exploding jungle, the Vietnam setting, the foreboding song by The Doors, but then it suddenly jumps to a single soldier with a single mission and the proceeding storyline takes place on a much darker and more personal level. Captain Benjamin L. Willard narrates his journey up the Nung River to assassinate the infamous, renegade Colonel – Walter E. Kurtz. Very few films ever do justice to the book that inspired them, especially such a literary work as Heart of Darkness so all credit to Coppola for being able to transplant it to Vietnam and retain the depth and intrigue of the original novel.

The controversial Pasolini made four (epic) films in the 1970s. I find them tough to watch. They are unflinching, dark in subject matter, but above all, unbearably human. Watching Sado for the first time made me feel ill – to be honest I wasn’t expecting much, after reading the book I remember thinking that there’s no way this can be turned into a film without becoming some kind of poor quality hardcore porn flick. Turns out it can, but not only that, Pasolini has an extraordinary sense of disquiet so it’s not the individual acts of cruelty which feel sickening, but the oppressive nature of the whole thing. The Decameron whilst retaining Pasolini’s trademark approach to sex and nudity is certainly less graphic, but no less powerful. Based on Boccaccio’s collection of short stories, Pasolini creates one of his most straightforward and honest films. The painterly nature of the film (Pasolini even plays the part of late Gothic, Florentine painter Giotto) is nothing less than sublime in the truest sense of the word – inspiring awe through fear.

I rarely watch Chabrol films. Perhaps he shouldn’t be on this list at all, but then again I rarely listen to Evan Parker’s Conic Sections and that’s a sure beast of an album, so rare isn’t necessarily bad. It’s not that I find Chabrol’s films particularly intense in a Tarkovsky or Resnais-esque manner, but I find them particularly unnerving without any real breathing space. So I chose Les Bonnes Femmes because being an early Chabrol flick it has more of a New Wave charm, although depending on your point of view it’s also Charbol’s most biting film, fully exploiting his sharp sense of irony and cynicism to throw everything back at the viewer.

And just when I thought films had completely moved away from the all embracing, no holds barred, psychological examination of a single figure, There Will Be Blood comes along and kicks me where it hurts. So this is what happens when you get that magical click between actor and director. Because Daniel Day Lewis really gives Paul Thomas Anderson something along the lines of what Klaus Kinski did for Werner Herzog in Aguirre: Wrath of God. Slowly worked towards a melting frenzy is just what I enjoy in my power-crazed characters and Daniel Plainview hits the mark completely. A far cry from the perhaps self-indulgent Magnolia, but nevertheless Anderson isn’t a director afraid to take risks.

Haneke is one of those directors who have a strange knack for delivering powerful slices of an often decaying family life that hit the viewer with an uncanny sense of unease. Hidden was like an intense shot of adrenalin, brutal and straight to the point. Time of the Wolf let things unravel with unease in its post-apocalyptic setting. But Code Unknown is the high point in his deconstruction and collapse of the family environment in a world where communication seems to have completely broken down. If only he hadn’t remade Funny Games to suit the Hollywood criterion, but perhaps he needed the money?

Who is Sergei Parajanov? Good question. He was one of many suppressed Soviet Russian filmmakers that refused to adhere to the conventions of Social Realism. He also had a passion for Pasolini, Tarkovsky and Fellini and as a result his films are like a combination of all three, but no second rate imitation and amazing in their own right. "Beauty will save the world," he once said. Watch any of his films and maybe you’ll begin to understand why. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is a deeply symbolic, folkloric, magical tale of lovers, jealously and betrayal, slipping between dream and reality like every good fairy tale.

The anti-Hollywood filmmaker par excellence. Everything one can possibly hate about Hollywood is nowhere to be seen in Deren’s experimental short films, which were artistic, creative, intelligent and above all else compellingly enigmatic. One thing I find so fascinating about Deren’s films is the beautiful dance-like camerawork and sense of rhythm and space. Deren was also a dancer/choreographer which no doubt helped considerably, but there’s also a wonderful poetry to her shorts that few filmmakers ever achieve. Meshes of the Afternoon is probably her most famous film (incidentally Teijo Ito created the music), but I think it’s also her most perfect combination of symbolism, movement and experimentation.

Hurrah for dystopian future worlds, escapist, dreamy, black comedies with flying men, Rube Goldberg machines, facial stretching and credit card obsessed robots. When you watch a Terry Gilliam movie, you know that nothing is going to be the same again. Imagination always wins the day. Oh and there’s also the satirical point of view.

And yet another film about the enduring power of human love – and this is silent film at its best with Murnau at his peak. Sunrise may well be the most influential film of all German Expressionist cinema (but there’s also Lang’s Metropolis so it’s hard to say). This is a film about love with all its sticky problems (and I don’t necessarily mean bedroom ‘sticky’), but mostly devoid of melodrama, there is a powerful realism to Murnau’s story that takes account of the inherent difficulties two people face when it comes to expressing themselves. And watching this film in retrospect of 80 years of cinema, its influence is remarkable. Read more...